Feminine, Feminist and Sinister:

Leonora Carrington, Remedios Varo and Occult Imagery

As Subversive Narrative Strategies

II.

In the later part of the 19th century, the Symbolists raised questions about art and society that had lasting effects on Western culture. Symbolism addressed the psychological concerns related to art production in all types of media, and “contributed to the twentieth-century view that art should be about ideas, and not simply about appearances.”[1] Symbolists, like other modernists – including Surrealists – were iconoclasts who wanted to overturn the established visual imagery of Academic realism. Symbolists furthered their rebellion by questioning traditional institutions such as the Church. Unearthing the paganism that had been sublimated by Christianity, they found creative outlets in the “archaic, occult and daemonic.”[2] For the Symbolists, use of this imagery was part of the same cultural trends that predominated among European cosmopolitans in the last decades of the nineteenth-century: a general breaking down of sanctions against blasphemy, exemplified in the séances and alternative religions popularized by Madame Blavatsky and others. According to Nadia Choucha, in Surrealism and the Occult, “In the [Symbolist] period, forms of highly aesthetic Catholicism and Satanism were popular artistic fashions, rather than serious ideological stances. Satanism in particular, offered a means of protest of society, especially the taboos of sex, death and religion.”[3] From these provocative foundations – exemplified by a work such as Le Calvaire, from Félicien Rops series Les Sataniques (Fig. 1) – the Surrealists created an entirely new mythology based on the occult and early twentieth-century research into archaic religions.[4]

Fig. 1: Félicien Rops, Calvary (Le Calvaire, from Les Sataniques), 1882

Another thread that runs through Symbolist and Surrealist ideology is the Romantic ideal of expressing through art the essence of the individual. As Maurice Denis famously proclaimed in Nouvelles Théories, “Le Symbole … prétend fair naître d’emblée dans l’âme du spectateur toute la gamme des émotions humaines par la moyen de la gamme de couleurs et des formes.”[5] Symbolists considered this elusive process of illuminating the submerged to be something akin to magic. The manifestation of a psychological state into a work of art took on alchemical overtones. In effect, the Symbolists believed that their ability to outwardly express hidden states gave “to art the power of divination, and thus Symbolism [was] an occult art.”[6] The Surrealists took this focus on externalizing interiority even further, by teasing out subconscious imagery through games and exercises, and by their emphasis on self-portraits and landscapes that attempted to convey abstract mental states.

The central importance of the female muse in Surrealist art also has antecedents in the work of the Symbolists. Celia Rabinovitch states, in Surrealism and the Sacred, "A new woman appears iconographically in the fin de siècle movement towards decadence. From Baudelaire and Nerval, the female image becomes colored with daemonic power as elemental and natural, or as evil and unnatural. Baudelaire held to the nineteenth-century view of women as closer to animals and children and therefore less moral than men… On the other hand, Nerval imbues his images of women with the sacred power of the goddess and the muse. These conflicting views merge in the new image of the quintessential woman as the seductive femme fatale, the mystical alluring sphinx of symbolist art [sic]." [7]

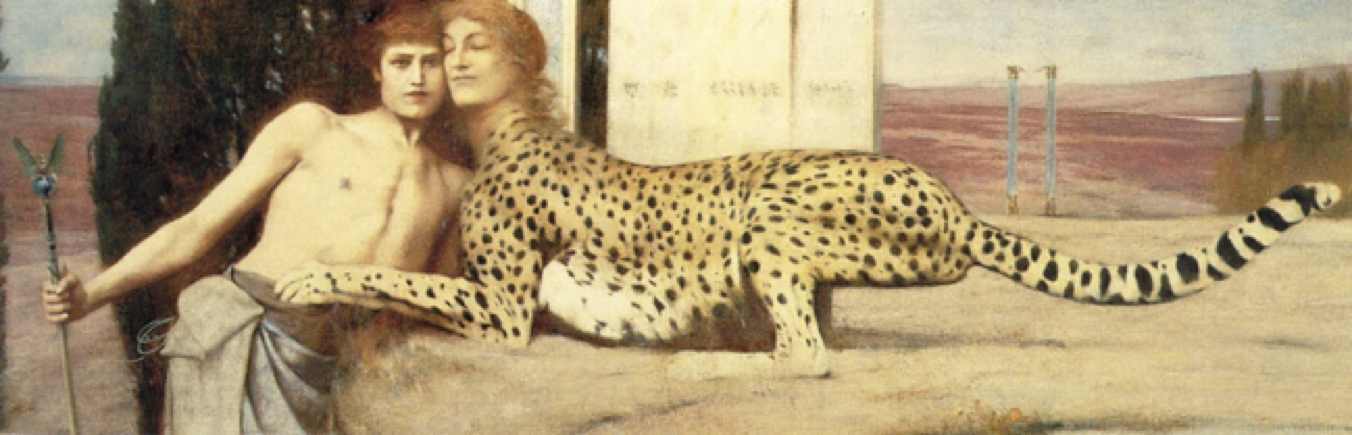

Fig. 2: Fernand Khnopff, The Sphinx, or The Caress (Die Zärtlichkeit der Sphinx), 1896

This misogynistic view of women as primitives, espoused not just by Baudelaire but by men (and women) throughout history, will be addressed in more detail later, but he new aspect of these depictions – the powerful imagery invoked by the femme fatale/sphinx or angelic muse – was revolutionary. In paintings like Fernand Khnopff’s Sphinx (Fig. 2), for the first time since the witchhunts of the Reformation, a totemic feminine power was acknowledged outside of the realm of the traditional sexualized object of the male gaze.[8] These depictions, however, were not without their problems. The dichotomy of “pure and spiritual virgins or castrating femme fatales”[9] left little room for authentic portrayals of ordinary women: while sublime goddesses were depicted as human women, the femme fatale “often took the form of the sphinx, chimera or harpie [sic].”[10] The Surrealists, who in turn played more loosely (and sometimes violently) with female imagery, presented the dichotomy as that of femme enfant and femme sorcière, and – most importantly – made women uniquely central to the creation of their art.

[1] Nadia Choucha, Surrealism and the Occult: Shamanism, Magic, Alchemy and the Birth of an Artistic Movement (Rochester: Destiny Books, 1991), 4.

[2] Celia Rabinovitch, Surrealism and the Sacred: Power, Eros and the Occult in Modern Art (Boulder: Westview Press, 2002), 202.

[3] Choucha, Surrealism and the Occult, 17.

[4] Rabinovitch, Surrealism and the Sacred, 10; and Choucha, Surrealism and the Occult, 3.

[5] Maurice Denis, Nouvelles théories: Sur l’art moderne, sur l’art sacré (Paris: L. Rouart et J. Watelin, 1922), 176: “The Symbolist… aims to immediately engender in the soul of the viewer the entire range of human emotions through a variety of colors and forms.” Translation mine.

[6] Choucha, Surrealism and the Occult, 19.

[7] Rabinovitch, Surrealism and the Sacred, 72.

[8] Ibid., 205.

[9] Choucha, Surrealism and the Occult, 16.

[10] Choucha, Surrealism and the Occult, 16.